I recently spoke to Wired UK about our experience with the Cutwail botnet for their article on “The Rise and Fall of the UK’s Biggest Spammer”. I thought it might be of interest to look in more detail at how the botnet works, how we identified it, and its eventual demise.

DNS requests

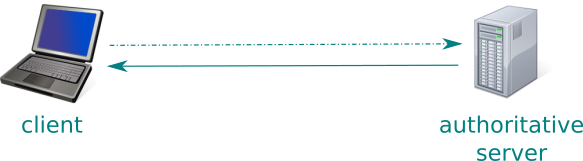

Before we get started we need a quick primer on DNS. Usually when a client (e.g. a desktop PC or laptop) needs to translate a humanly recognisable domain name into a machine usable IP address it makes a DNS request. Most commonly it is done via a proxy server which is provided by whoever is providing your internet access, or via a “recursive DNS service” like Google’s 8.8.8.8 or OpenDNS. It is the address of this proxy machine that we see at the authoritative servers we run.

Occasionally we see requests which don’t look quite right according to the DNS protocol; certain flags which we expect are missing, or those which we do not expect are present. Often these are one-off queries and occur in such low volumes that we do not worry about them; sometimes however they are anything but low volume. Turing allows us to see both of these scenarios and to drill down to see the details of what is going on.

One such group of requests was noticed back in 2014; it had a particular fingerprint and was often associated with large numbers of MX requests; that is a question we get asked when a client is trying to deliver an email. At times the signal from this particular source would dominate all of the traffic we were seeing across our infrastructure. Some further analysis, including a careful dissection of malware samples, confirmed the identity of the signal to be from “Cutwail” a botnet which had been around since 2007. This particular malware has code to perform its own DNS lookups (rather than defer them to the operating systems default method). Luckily for us whoever wrote this code either didn’t read, or didn’t understand, the relevant standards (as recorded in RFCs) and so we are left with a client which talks directly to our servers with a fingerprint that we can track with turing.

What is going on?

A machine infected with Cutwail sends spam; it gets lists of emails to send and recipients to send to which it works through; finally returning a report on how many it managed to deliver. So what we have is the ability to track one source of spam as it attempts to deliver email into the .UK namespace. We can plot the number of requests this botnet was making, and also the number of individual clients involved. (To avoid problems with NAT and IP mobility we regard an IP as being Cutwail if we only see requests which match our fingerprint and none that do not match over the previous 24 hours.)

What we see

We can plot two years in the life of this botnet as follows:

Here each dot represents the traffic from the botnet on a particular day. The size of the dot represents the volume of queries and the colour represents the quality of those queries; redder dots showing periods where the majority of domains requested did not exist. (Spam lists are often polluted with old or just plain garbage addresses; sometimes people try replacing the “.com” in a well known domain with “.co.uk” or “.uk” which often results in a non-existent domain.)

At it’s busiest the botnet was making 1 Billion queries per day across just two of our nameservers, which puts the total number of queries over our infrastructure at around 8 billion assuming that they are evenly distributed. We can also plot how many unique IP addresses we see participating at any one time alongside the level of activity from the botnet.

We can see from this that although there is a correlation between the daily volumes and number of unique IP addresses seen there is also a period where, despite the numbers shrinking, the level of activity was increasing. This could be due to a number of factors and the most likely are not technical. For example the botnet owners may have dropped their prices and so found more customers, or it may have been taken over by owners who were less careful about drawing attention to its existence… From our data we can only say that through February to June in 2014 Cutwail was as busy as we ever saw it despite its daily size dropping below 50,000 addresses from the peaks of 200,000.

The reasons for its decline are also not immediately obvious to us from our data; one thing that we do know however is that around this time the NCA, FBI and Europol coordinated an effort (along with some security firms) known as “Operation Tovar”. This operation was aimed at seizing control of the Gameover ZeuS botnet and we know that Cutwail was being used to spread malware, Gameover included; so it is possible that it also disrupted the Cutwail command and control system. It is also possible that the knock that Gameover took meant that there was just a lot less work for Cutwail to do. Another possibility would be a new variant of Cutwail was spreading which had the flaws in its DNS code fixed; this would not appear to be the case as, until recently, we were not seeing large spam runs which did not match Cutwail’s signature.

We still see some traffic which has this particular signature today; but at a few tens of millions of requests per day across all of our infrastructure. This could either be Cutwail still hanging around or possibly a new botnet which grew out of the same codebase; there is of course option three which is an entirely new piece of malware that has the same logic and same flaws.